Scottish Smallsword

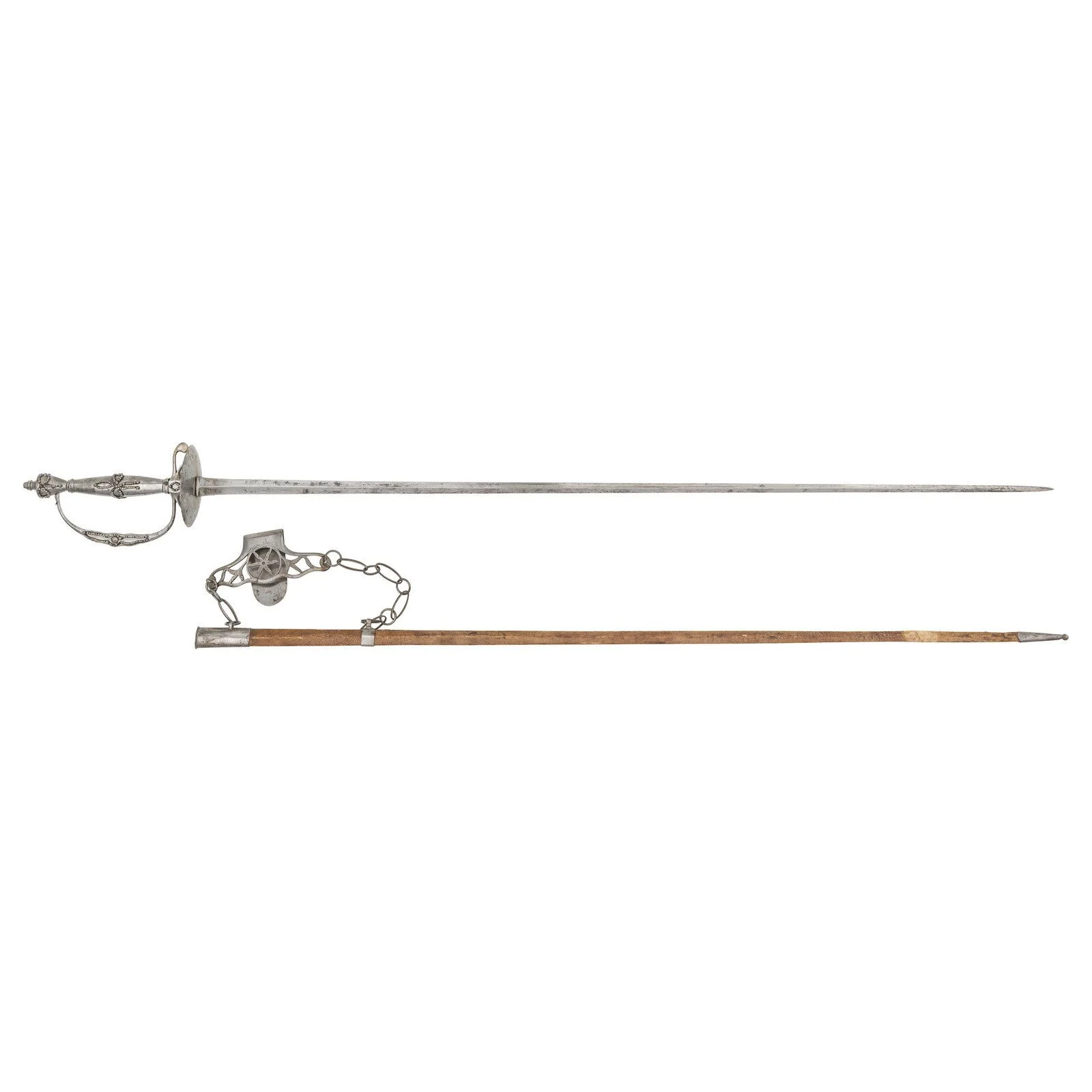

The Smallsword was a thrusting-only weapon developed in France in the second half of the 17th century. The blade was relatively short, light and stiff, and the hilt consisted of a small shell- or disc-shaped guard, a grip, usually (but not always) a knucklebow, and often (but not always) small rings between the grip and the shell of the sword, which were a vestigial design feature from the grip used in Renaissance rapier combat, with the finger over the crossguard.

The long, heavy Renaissance rapier was never popular in Scotland, even among the Lowland gentry. Although the term “rapier” continued to be applied to the Smallsword well into the 19th century, the Smallsword is a very different weapon to the Renaissance Rapier. The Rapier was a very long “thrust and cut” sword, about as heavy as contemporary cutting swords. Although the weapon and the systems of fence associated with it strongly emphasised the thrust, it was also capable of delivering effective cuts and easily deal with the blows from shorter military-style swords. Because of its length, it was usually wielded in conjunction with a dagger in the off hand, or some other device, which provided some protection in close fight.

The Smallsword quickly spread from France to the British Isles. The success of the Smallsword can probably be attributed to fashion; when the court Charles Stuart II returned to England from continental exile in 1660, he brought with him many French fashions, including the “Court Sword.” Whether it made its way to Scotland via the English court, or was imported directly from France is impossible to say, but the Scots, particularly the nobility, had a strong tradition of education in France, and it is striking that the word “Smallsword,” like “Broadsword,” also appears to be a Scottish word, first cited in Hope’s 1687 manual, The Scots Fencing Master.

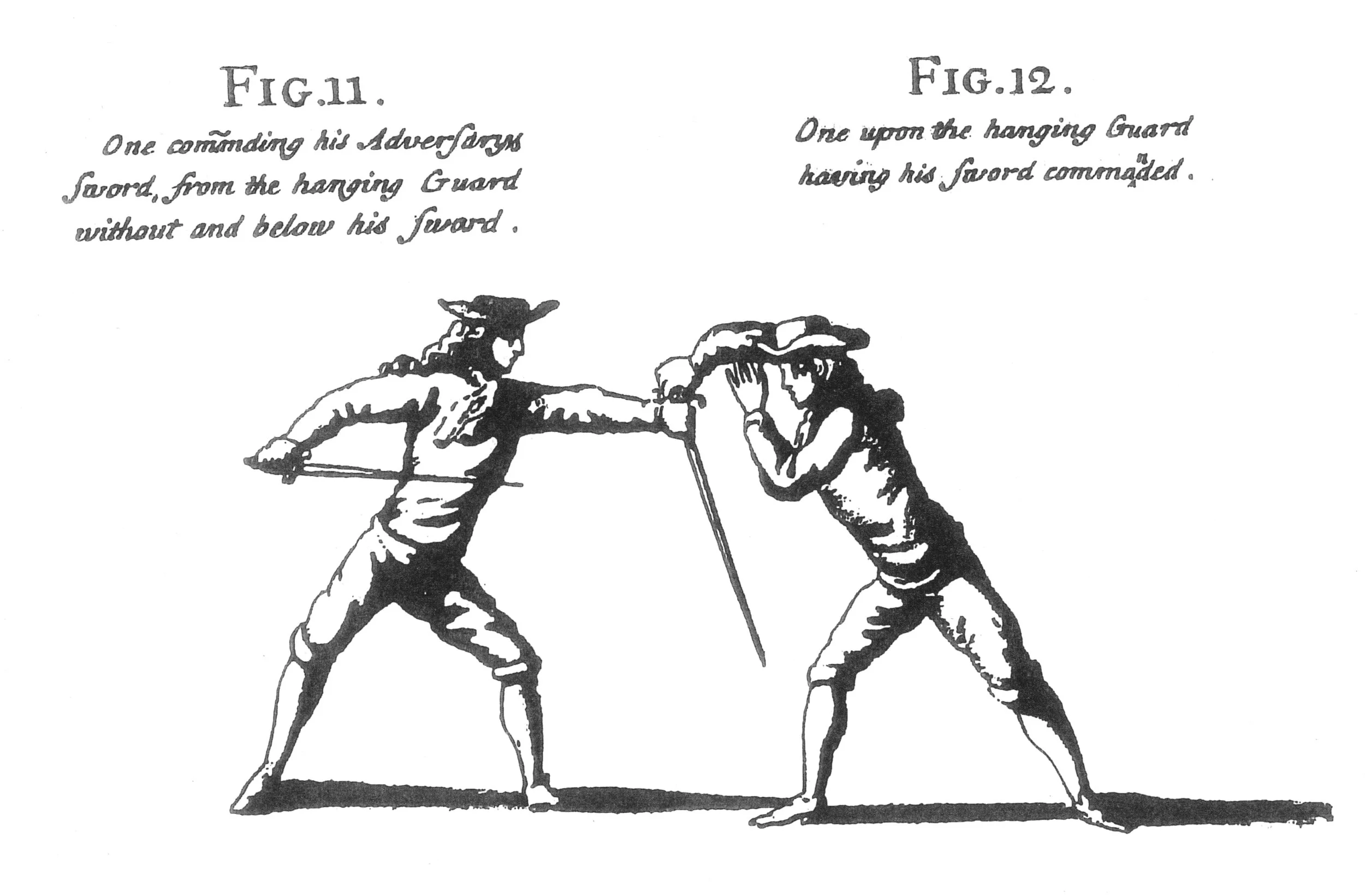

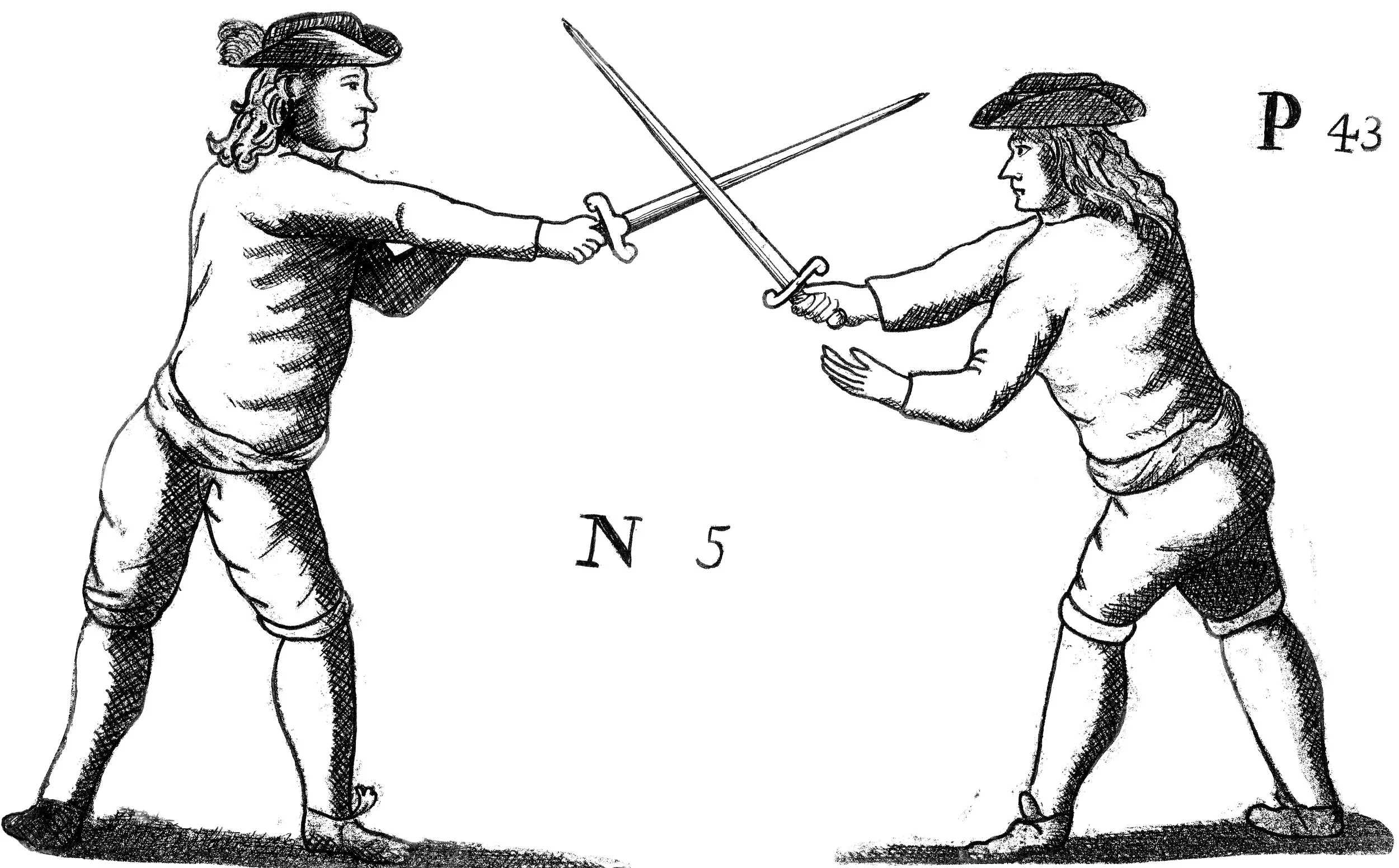

The most important manual for Scottish Smallsword is Donald McBane’s The Expert Sword-Man’s Companion of 1728. Unlike Hope, McBane was not nobility or a gentleman, but a low-born soldier, gambler, pimp, and general all-round rake. Of all historical Smallsword manuals, McBane’s is certainly the most practical. His colourful life gave him a wealth of experience in practical life-and-death combat with the Smallsword, which no other author, British or French, could claim. His method is simple, straight forward, and differs with the common French method on some important points. The influence of the Broadsword on his system is clear. McBane’s brief instructions for Backsword match almost exactly with that of Thomas Page in 1746, and the intimate relationship between the Smallsword and Broadsword claimed by nearly every British Smallsword text makes a thorough understanding of Broadsword vital to mastering the Smallsword.